By Ralph Blumenthal

The New York Times

November 12, 2007

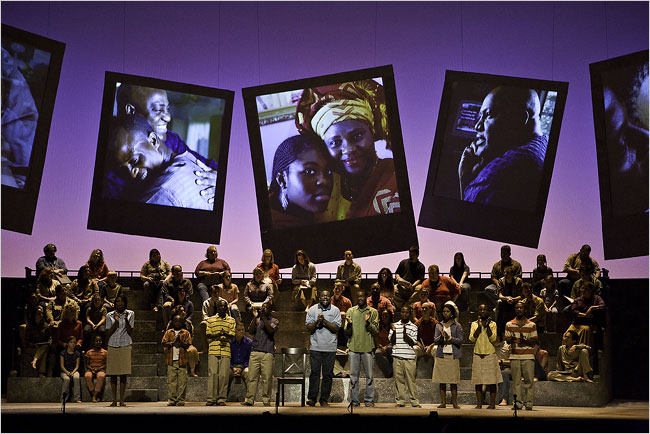

A group of Congolese immigrant singers rehearsing “The Refuge,” at Houston Grand Opera. The work recounts the immigrants’ stories in their own words. Credit Michael Stravato for The New York Times

A group of Congolese immigrant singers rehearsing “The Refuge,” at Houston Grand Opera. The work recounts the immigrants’ stories in their own words. Credit Michael Stravato for The New York Times HOUSTON, Nov. 11 — With brickbats flying over border issues, the Houston Grand Opera put immigration center stage this weekend in a dramatic outreach to the more than 1 million foreign-born residents here in the nation’s fourth largest city.

The musical and civic event was “The Refuge,” the company’s 36th world premiere and a commission celebrating not only the 20th anniversary of its Wortham Theater Center but also Houston, where more than one out of five people “are not from here,” in a signature phrase of the new work.

In an elegiac finale, the singers, including five young Congolese brothers new to the opera stage, proclaim: “We are you. Our stories are your stories.”

Dramatic oratorio, musical drama, opera vérité or some new synthesis, performed against a stark backdrop of shifting photo portraits, the collaboration by the award-winning composer Christopher Theofanidis and the librettist Leah Lax, a Houston writer, drew standing ovations and bravos at its two performances on Saturday. (It is scheduled for two more performances in May at the Miller Outdoor Theater here. )

The 90-minute work proceeds without intermission through seven tableaus in which the company’s regular soloists, choristers and orchestra, joined by non-Western musicians and some of the immigrants themselves, recount the ordeals that brought people here from Africa, Vietnam, Mexico, Pakistan, India, the former Soviet Union and Central America. They are heard speaking their own words as tape-recorded by Ms. Lax in hundreds of interviews.

Some clearly came illegally, but the work is apolitical, said Ms. Lax, 51. “There’s no judgments,” she said, “just real people telling their story.”

Mr. Theofanidis, 39, agreed. “My main goal is to delight, connect with the humanistic impulse,” he said.

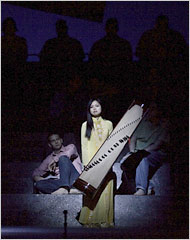

Julie Trinh Dang with a 16-string Vietnamese dan tranh. Credit Michael Stravato for The New York Times

Julie Trinh Dang with a 16-string Vietnamese dan tranh. Credit Michael Stravato for The New York Times As the debut production of Song of Houston, a broad effort to bind the innovative 52-year-old Houston Grand Opera to the community through a series of cultural events, Saturday’s performances, including a free matinee, attracted many first-time operagoers, some in native dress.

One was Marie Ndoole Mukule, who fled Congo and now works for a dental instruments company in Houston. She had five sons singing in “The Refuge,” and a sixth, Ezechiel, 7, was eager to follow suit. “I want to be a singer,” he said.

Anthony Freud, the opera company’s general director and a former director of the Welsh National Opera, welcomed immigrants from the stage. “You are a true inspiration to us all,” said Mr. Freud, who commissioned the work shortly after joining the company last year, replacing David Gockley, its director for 25 years.

Mayor Bill White, who was just re-elected to a third and final two-year-term and had helped the opera company connect with immigrant groups, hailed the effort “for putting the mirror of art to this great community.”

Houston is one of the nation’s most diverse cities, behind only Miami, Los Angeles and New York in foreign-born population, with nearly 22 percent. It also became a major resettlement center after Hurricanes Katrina and Rita in 2005, receiving an influx of a quarter-million uprooted people, although their stories are not part of the production.

“The Refuge” grew out of a 2006 dinner Mr. Freud had with an opera patron who recounted the grim tale of a Salvadoran refugee she knew. Mr. Freud said it opened his eyes to a way of engaging a potential audience to whom, he said, “opera has been completely irrelevant — until now.”

Christopher Theofanidis, composer of “The Refuge.” Credit Michael Stravato for The New York Times

Christopher Theofanidis, composer of “The Refuge.” Credit Michael Stravato for The New York Times Mr. Theofanidis, the composer of widely performed orchestral works including “Rainbow Body” and winner of the Rome Prize, a Guggenheim Fellowship and other awards, had an emotional tie to the project: His father, also a musician, came from Greece.

Ms. Lax, whose grandparents emigrated from Eastern Europe, was known for her collaboration with the photographer Janice Rubin on “The Mikvah Project,” a book and traveling exhibition exploring the intimate world of the Jewish ritual bath for women. Ms. Rubin contributed the photo portraits for “The Refuge.”

At first Ms. Lax had trouble getting immigrants to put aside their suspicions and speak freely. But she was able to assemble a 150-page manuscript filled with what she called “zingers,” as when one of the Mukule boys declared: “No, we don’t miss Africa! Just all the time we want to sing our songs!”

The Salvadoran woman, Eva, whose tale inspired Mr. Freud to commission “The Refuge,” flees home after a gang murders her mother and one of the robbers rapes her. She is smuggled into the United States and sends for her young son, who is transported to the border hanging onto the undercarriage of an 18-wheeler. But the smugglers betray the child to the Border Patrol, and Eva is lured out of hiding to claim him.

Rebekah Camm, a company soprano, sings Eva’s response. She may be deported, but she will return. “I can do this,” she vows, “because I know how.”

“The Refuge” ends with the chorus singing, “Walking, walking, day and night,” and concludes with a cry of triumph: “We are here now too.”